We move Southwards to the wealthy suburb of Bangsar. Property prices skyrocket, yet vacant lands abound. Economic theory predicts that in an efficient economy, Price increases with diminishing Supply or increasing Demand. If there is still supply of undeveloped lands, does this mean people are demanding vacant residential plots? Why?

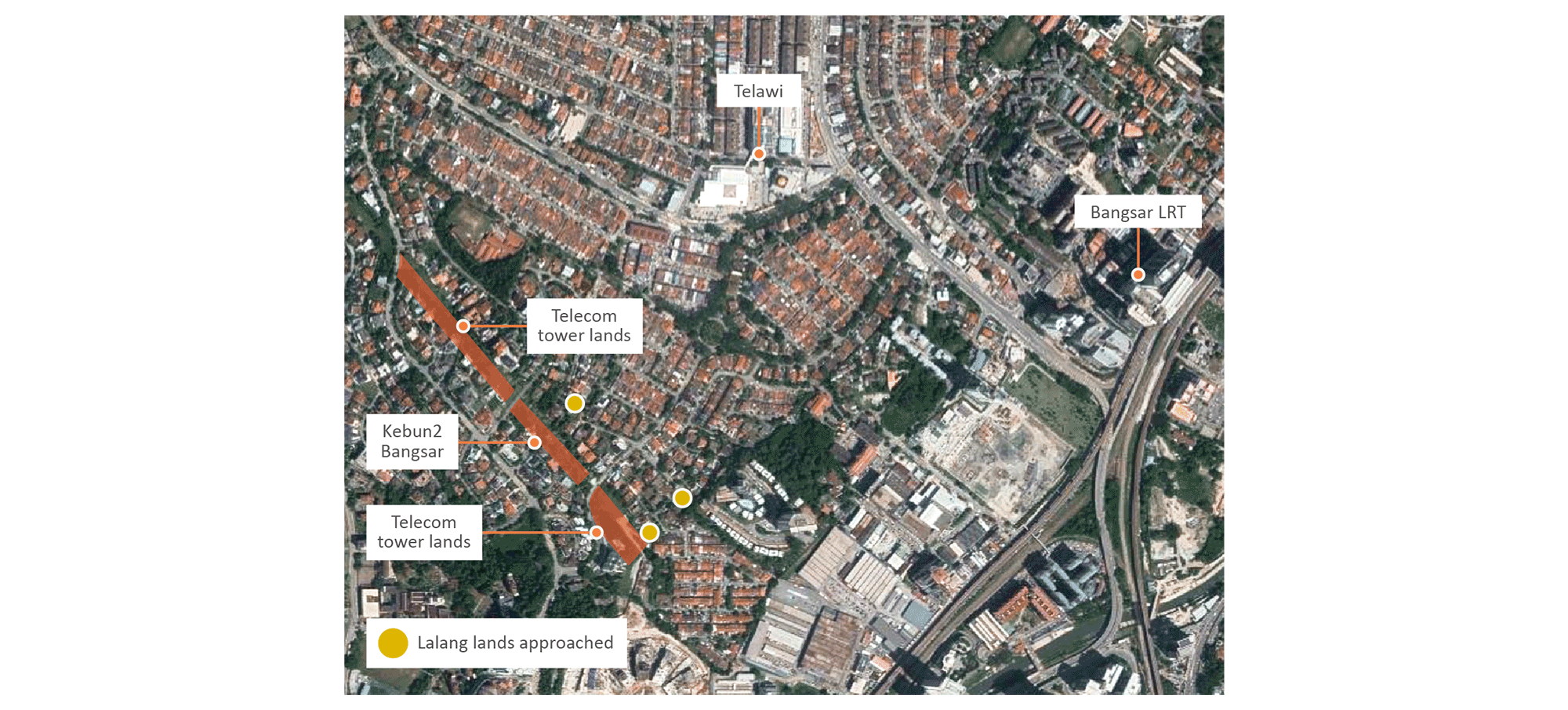

I explore two types of vacant lands: public and private. I centre around (1) Kebun-Kebun Bangsar’s utopia of “upcycling” vacant TNB land into a food farm and (2) Vacant residential lands nestled between the bungalows of Bukit Pantai and Bukit Bandaraya. These two example approaches to vacant lands illustrate radically different understandings of land use centred around efficient use of Emptiness.

If chapter 1 argues that there is no Pristine Nature, this chapter observes two categorically “unpristine” natures in Kuala Lumpur, and provides thick description of the potentials and pitfalls of co-nurture. Exploration of Kebun-kebun Bangsar and Lalang Lands put forward some intended and unintended occurrences in Human-Nature relations. These two different types of land uses in this same neighbourhood illustrate how Green/Grey spaces do not always map onto Sustainable/Unsustainable spaces. Furthermore, human desires and logics — whether land ownership legalities, imaginations of ideal human-nature relations, or market logics — will always structure the shapes and sustainability of our “Greenspaces”.

Reflections

Green-city definitions (typically measured in “green” coverage) may miss opportunities for unconventional sustainable land practices.

Not all that is Green is sustainable. Not all that is Grey is unsustainable.

What are the boundaries of public/private agendas? There are opportunities for thinking of sustainable urban planning beyond public space.

We move Southwards to the wealthy suburb of Bangsar. Property prices skyrocket, yet vacant lands abound. Economic theory predicts that in an efficient economy, Price increases with diminishing Supply or increasing Demand. If there is still supply of undeveloped lands, does this mean people are demanding vacant residential plots? Why?

I explore two types of vacant lands: public and private. I centre around (1) Kebun-Kebun Bangsar’s utopia of “upcycling” vacant TNB land into a food farm and (2) Vacant residential lands nestled between the bungalows of Bukit Pantai and Bukit Bandaraya. These two example approaches to vacant lands illustrate radically different understandings of land use centred around efficient use of Emptiness.

If chapter 1 argues that there is no pristine nature, this chapter observes two categorically “unpristine” natures in Kuala Lumpur, and provides thick description of the potentials and pitfalls of co-nurture. Exploration of Kebun-kebun Bangsar and Lalang Lands put forward some intended and unintended occurrences in Human-Nature relations. All relations are frizzy, uneven, and complex; there is no relation without compromise.

Working with Human-Nature

In popular discourse, we find a war happening between human and nature. We hear of logging companies felling forests, traditional lands being encroached, pangolins being hunted. The stories we circulate to each other are built on the frames through which we understand the world. We repeat out loud: Human and Nature are starkly opposed. For one to grow, another must secede.

We mirror these frames in our nostalgia to fix that which we have lost: We gazette land away from Humans for Conservation. Financial institutions claim ESG investment as giving up profit for Nature. Urban farms reclaim land from private ownership.

There is a sense that sustainability — a “greener” urban landscape — means compromising on Humans for Nature. These are useful strategies, but they are not our only strategies. A different appreciation for the urban-ecology di sekitar kita can help us forge a path from understanding Human-Nature as compromising to understanding Human-Nature as co-nurturing.

Public Transmission: Kebun2 Bangsar

A strip of transmission tower land (owned by TNB) cuts through Bukit Pantai (see map). Due to concerns over high voltage power lines, a land buffer separated residential lots from the towers, and there it slept undisturbed and overgrown for roughly four decades. In 2016, after much conversation with DBKL, the nonprofit Kelab Kebun Bangsar was given management to develop 2.5 acres of the land. The goal is “a people-centric permaculture community garden that envisions people from all walks of life to come together to work with, rather than against nature [emphasis added]⁸”.

What does it mean to work with Nature?

Kebun-Kebun Bangsar (KKB) appears unexpected. The entrance sits on the outside bend of a right turn curve. Most visitors enter KKB by turning off of Lorong Bukit Pantai onto a hot gravelled car park. On the right, you see large compost piles for visitors to drop off their waste. Ahead, there is a large brick wall overgrown with creepers; you cannot see what is behind the wall. There are two gates: (left) one small metal door with a with a bell chime and an instagram bench, and (right) an outwardly swinging large gate for trucks.

Only the human gate is unlocked (from 9-6pm excluding Mondays). Step inside, and the temperature suddenly drops. Bees and butterflies flutter. Mix cultivations of flowers and vegetables reach out from metal containers to greet you. You are charmed by gentle peacocks and chickens. They pok pok pok as you read a sign: “This garden is made of HOPE”.

You are led by a metal trail up the hill, following terraced vegetables on your left. On the right, you see a variety of ecosystems and permaculture: tilapia ponds, geese, edible flower gardens, paddy fields, swamplands, and even a hydroponic house on a ledge amongst neatly trimmed grass.

⁸ Sign post of proposal in Kebun Bangsar storage

There are various words that KKB self-describes as: kebun, garden, farm. I wonder what arrangement of Nature differentiates a farm from a park from a forest. Is HOPE the secret ingredient that transforms the wild weeds of transmission towers into kebuns that work with Nature?

I search for KBB founder, Seksan, in hopes he can provide the Authoritative Description of KKB’s vision. But the Kebun is empty, except for two men bustling up and down the hill with wheelbarrows.

“Encik, Seksan ade tak?

“Baru balik la. Panas!”

“Eh tak banyak orang la. Biasanya, ade lebih orang di sini ke?”

“Mmmm.. Saturday la. Saturday ade baaanyak voluntir. Kalau hari macamni panas-panas, pasti takde orang la [laughs]. Diaorang voluntir tak boleh tahan panas.”

“Ohhh okok, apakah yang volunteer buat kat sini?”

“Voluntir… pada hari Sabtu, mereka tanam-tanamje lah. Selain daripada itu, hanya kita dua orang saje. Kalau kita tukang kebun tak berada bila panas, sayur-sayur juga tak boleh tahan panas; kita kena siram. Ah! (briefly exasperated) Tapi diaorang volunteers lah! (Tone softens) Kita tak boleh control.”

For Mun, “tahan panas” is the category used to differentiate those who nurture and those who are nurtured. I wonder if the parallels he draws between plants and volunteers is intentional. But then he reiterates this category in describing skilled labour.

“Dah berapa lama kerja kat sini?”

“Lebih kurang 6 bulan. Dulu aku jual leather bags semua tu di Petaling Street, tapi tahun lepas March hilang kerja kerana MCO.”

“Suka kerja sini ke? Dulu pernah kerja Kebun tak?”

“Ah cari makan saje la. Tak pernah, tapi kampung saya jugak ada kebun. Kitaorang kampung tau tahan panas.”

Mun also uses “tahan panas” to associate his rural lifestyle with the skilled knowledge necessary to nurture urban green spaces such as KKB. In this conversation, he distinguishes worker/volunteers, human/nature, and rural/urban along kebolehan “tahan panas”.

It is not a stretch to say that for many visitors and volunteers, materialising HOPE via nurturing plants is a process of nurturing HOPE in themselves. This garden is made of HOPE, just as it publicly transmits HOPE for a “greener” way to organise human relations and land.

However, HOPE is materialised not solely by the practices of volunteers, but by the trucks that drop off food waste, the metal extractors for rebar and fences, the quarries for gravel parking, and all the razed weeds that held nutrients in the soil for four decades. Hand over forehead, I shade my eyes from the sun as I watch Mun wheelbarrow more vegetable scraps on this lonely hillside. “Mun, nak balik. Ma kasih cik” (for nurturing my soul this morning).

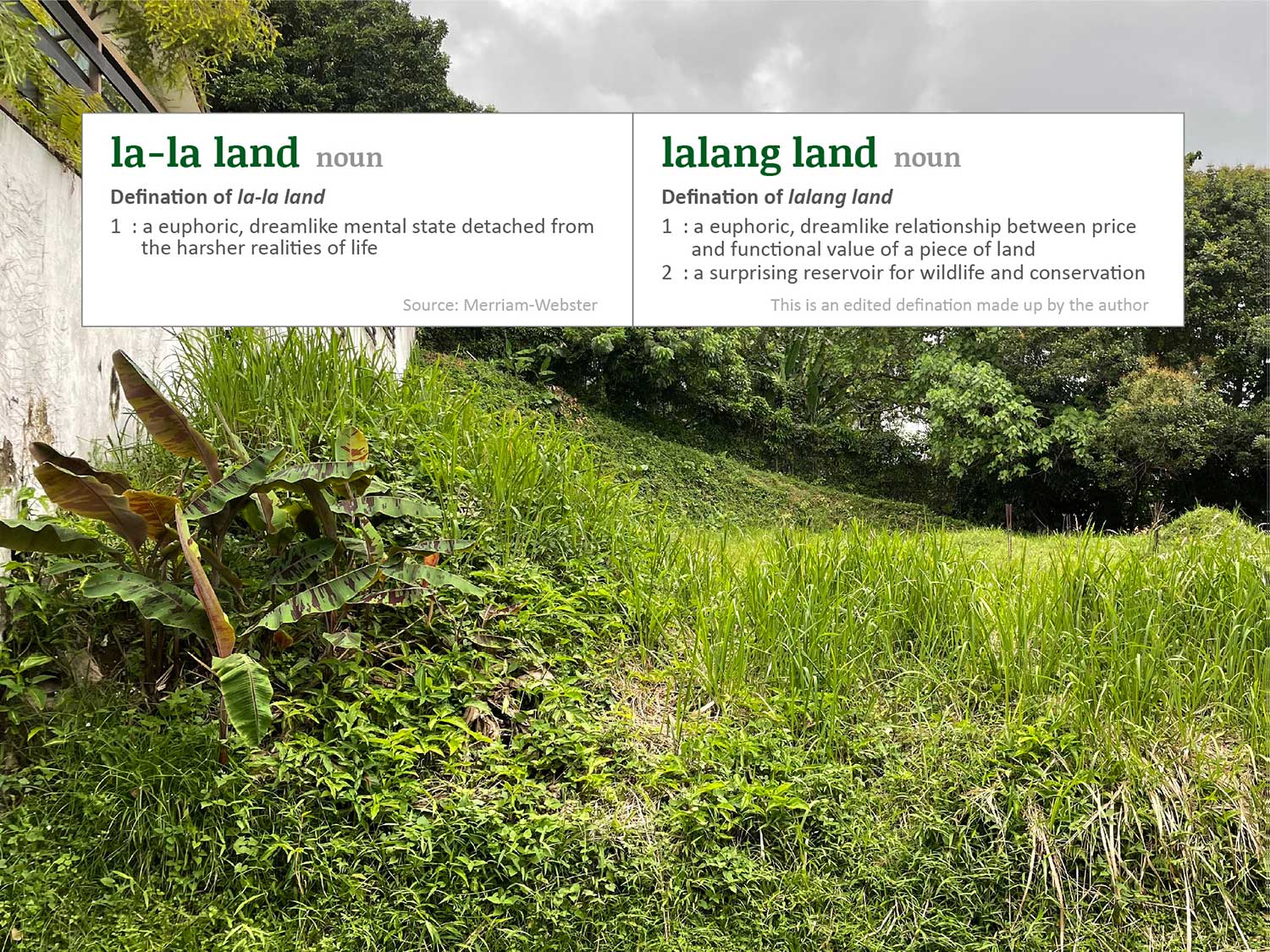

Private Transmutation: Lalang Lands

There is an unexpected sort of Conservation happening in Bangsar. A quiet but growing encroachment of wild lands upon this densely developed area of KL. I call these wild land ecologies: Lalang lands.

Lalang lands are found nestled between large bungalows or across bustling commercial streets. They pop up in the most unsuspecting of places with seemingly little rhyme or reason. Most take the form of meadow patches, while some have concrete poured over them. It is not uncommon to find fig trees. A small number have no human markers, but on most, you find a variety of territory markings, such as “FOR SALE: Adrian Tan” or “Car Park” (sometimes just a “P” in a blue box).

(One owner I contacted required me to send them my business card and website before they were willing to start any conversation.)

If not Humans, then what thrives in emptiness?

I approach the driveway and fence in search of inspiration. The semak is thick, and sticky pricks pull back on my shins. My untrained eyes cannot make an assessment on the ecological value of these sites. I don’t find much inspiration, so I do what I can, and take what I know how to value⁹ : some pretty looking “weed” plants my mum would like.

As I leav-

“Hey, got dog come out”

I try to snap a photo, but it shies and skitters away. I guess that it too, prefers privacy in its residence. Urban wildlife hide from our view, in the empty spaces vacated by owners, but also privately “gazetted” from other humans. How funny that these lands of ever increasing monetary value are left to be secretly exploited by plants, animals, and land owners who are at once there, but also not there.

⁹ Scientific ecology is only one way of relating to nature. But nature and its possible interpretations of value is not the domain of experts, it is also yours.

Discussion

- This chapter addresses emptiness, not because these example spaces are literally empty, but because these two spaces are perceived as empty containers waiting to receive meaning and development. KKB needs to perceive the transmission tower lands as empty land in order to invest upon it with new hopes/potential futures. Similarly, private owners leave land and houses empty, because of potential returns (which perhaps fuel other types of hopes and futures); one could say, private owners are planting a different sort of seed in their lalang lands.

We see two types of land transformations happening on the same Bukit Pantai: In KKB: from weeds into development; in Lalang lands: from development back into weeds. The forms of “development” are different of course. One is a kebun-park and the other is housing.

Perhaps we could consider weeds a point of transition between how humans change their material space. “Nature” here functions as a recycling point between different human imaginations of desirable ways to use space. In other words, empty weeds “hold space” for expression. It is a momentary time period where various claims over land use can be negotiated.

- A second thematic consideration brought up is these two distinct ways we work with Nature along the lines of private/public ownership. Conservation in the urban context differs from the rural context. One of the key differences is that private ownership in urban spaces (Lalang lands) are much well shielded from public claims on appropriate land use (example: KKB).

- A third thematic consideration is the blurry boundary between “Green” and “Grey” spaces. These two examples sit on the peripheries of “pure” nature spaces and “pure” human spaces; they are lands that are neither-human-nor-nature. Kebun Kebun Bangsar is “Green”, but is also incredibly intensive in terms of energy, material, and labour inputs. On the other hand, Lalang lands are these paradoxical “Grey” spaces, where it generates strong financial profit but only see passive human intervention. Lalang lands are much more materially defined by non-human interventions.

These ambiguous spaces add some nuance to typical narratives about conservation and green space: Green good, grey bad. Public good, private bad. It asks us to locate potential of working with nature in unconventional sites.

- Finally, a tangential but nevertheless key issue raised is: who’s voice do we consider Authoritative Knowledge of a project? Developmental research and projects that focus on “Community Leaders” sometimes overlook the heterogeneity of a community. By approaching gardener Mun instead of Seksan, the Kebun narrative perhaps took a very different turn. Perhaps something to be gained when we approach knowledge production humbly and un-authoritatively.

Conclusion

Chapter 1 in Mont Kiara argues that there are no Pristine Natures. It also suggests that we need the appropriate types of humans and developmental ideologies to have a symbiotic relationship with urban greenspace. This chapter builds on the last chapter by exploring two categorically “unpristine” natures where the relationship between human and nature are acknowledged. It interrogates two radically different developmental ideologies and relationships with land.

This second chapter contributes to contemporary urban planning conversations about “Green cities” by advancing conventional definitions of “green” beyond green coverage. The two different types of land uses in this same neighbourhood illustrate how Green/Grey spaces do not always map onto Sustainable/Unsustainable spaces. Furthermore, human desires and logics — whether land ownership legalities, imaginations of ideal human-nature relations, or market logics — will always structure the shapes and sustainability of our “Greenspaces”.

If this chapter explores possible intended and unintended human relationships with nature, the next chapter puts Nature in the driving seat. It asks, does Nature need saving at all?

by Teoh Jia Chern