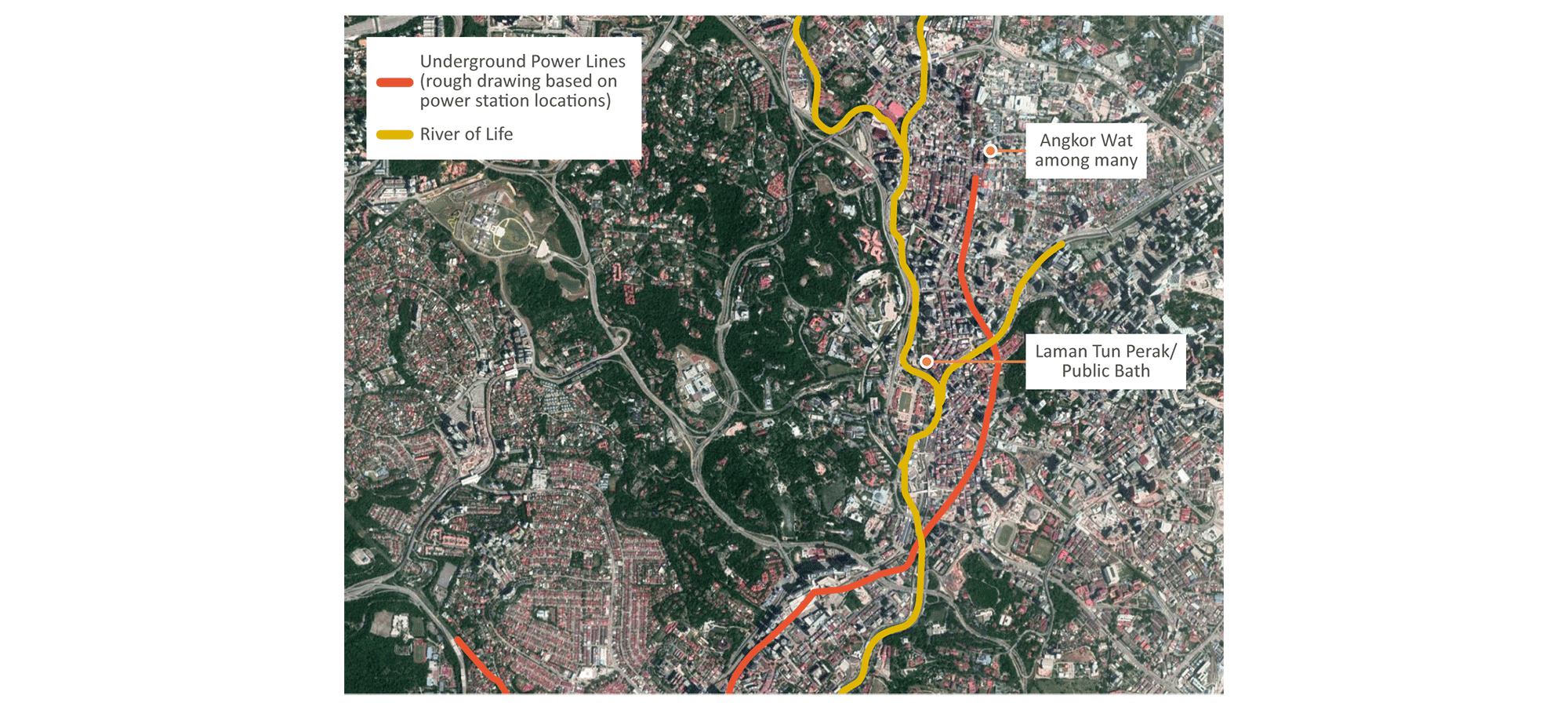

This chapter centres around (un)control(ability). Power lines move underground as we move into the city, and become harder to trace. If the previous essays touch on visible interventions to manage and control Humans and Nature, this chapter reads non-intervention (or abandonment) as a specific form of management. In the two sites observed for this essay, abandonment can simultaneously reflect the limits of human control and specific practices exclusion.

This chapter opens with a brief vignette about Nature overgrown upon abandoned buildings. It then explore the concept of enclosure through those who are trapped at home, and those who are trapped outside. These narratives occur over the backdrop of ThinkCity greening projects. Finally, I centre down to ThinkCity’s first project and its relationship with wild nature and wild humans.

Reflections

Develop a Green framework without the underlying assumption that Nature is the only things that needs saving.

Planning needs to recognise the uncontrollabilities of execution.

Not all public space is made for the public.

“Wah this building like so overgrown already. It’s almost like… what’s that place called? Angkor Wat haha. We should market Chow Kit become new Angkor Wat.”

“When people think of heritage conservation in Malaysia, we often compare ourselves to those western countries. But those western places just don’t understand the sheer power of nature in tropical countries like Malaysia. It’s way more work to conserve. You just can’t stop nature.”

“How long do you think it took for the building to be overgrown like this?”

“Probably less than 20 years.

This chapter centres around (un)control(ability). Power lines move underground as we move into the city, and become harder to trace. If the previous essays touch on visible interventions to manage and control Humans and Nature, this chapter reads non-intervention (or abandonment) as a specific form of management. In the two sites observed for this essay, abandonment can simultaneously reflect the limits of human control and specific practices exclusion.

Wildness as Kebebasan

The Buku Jalanan Chow Kit students are audibly downbeat. We are attempting to use community mapping to learn about how students understand space and their relationship with Nature. The project is not helped by Covid lockdowns shunting a walking project into zoom workshops in cramped homes. How do we understand space when we have no space?

C: Biasanya, bagaimanakah kau pergi jemput kawan? Guna kereta, ba-

A: Eh, mana ada pergi mana2? Bro, sekarang PKPD la, kita duduk rumah je.

We shift to asking them about the view from their window. And Fairul (pseudonym) shouts out, “KEBEBASAN”. Nature matters to the students, but not particularly in the “biodiversity” nor “carbon-neutral” frameworks advanced by urban planners. Instead, having public spaces like tamans and padangs were valued as a free social congregation space to play. A couple of older students used the River of Life path for running and exercise. Football was a favourite for girls and boys, and they would recount showing up at the Kelab Sultan Sulaiman padang to play with anyone who was there.

When discussing animals, they would bring up biawak, anjing, or ayam, but not from a biodiversity standpoint. It is also important to highlight that nature did not feel like a consistent category of concern to students. Birds were proxies for freedom. Dogs were talked about alongside “orang gila” or “uncle kedai” who were annoyances that chased them when students were out on the street. Seeing crocodiles and monitor lizards in the river were just the little spices of life. Nature was emblematic of Kebebasan, and you could almost sense a tinge of jealousy for the stray cats that wandered from house to house. Wild and free.

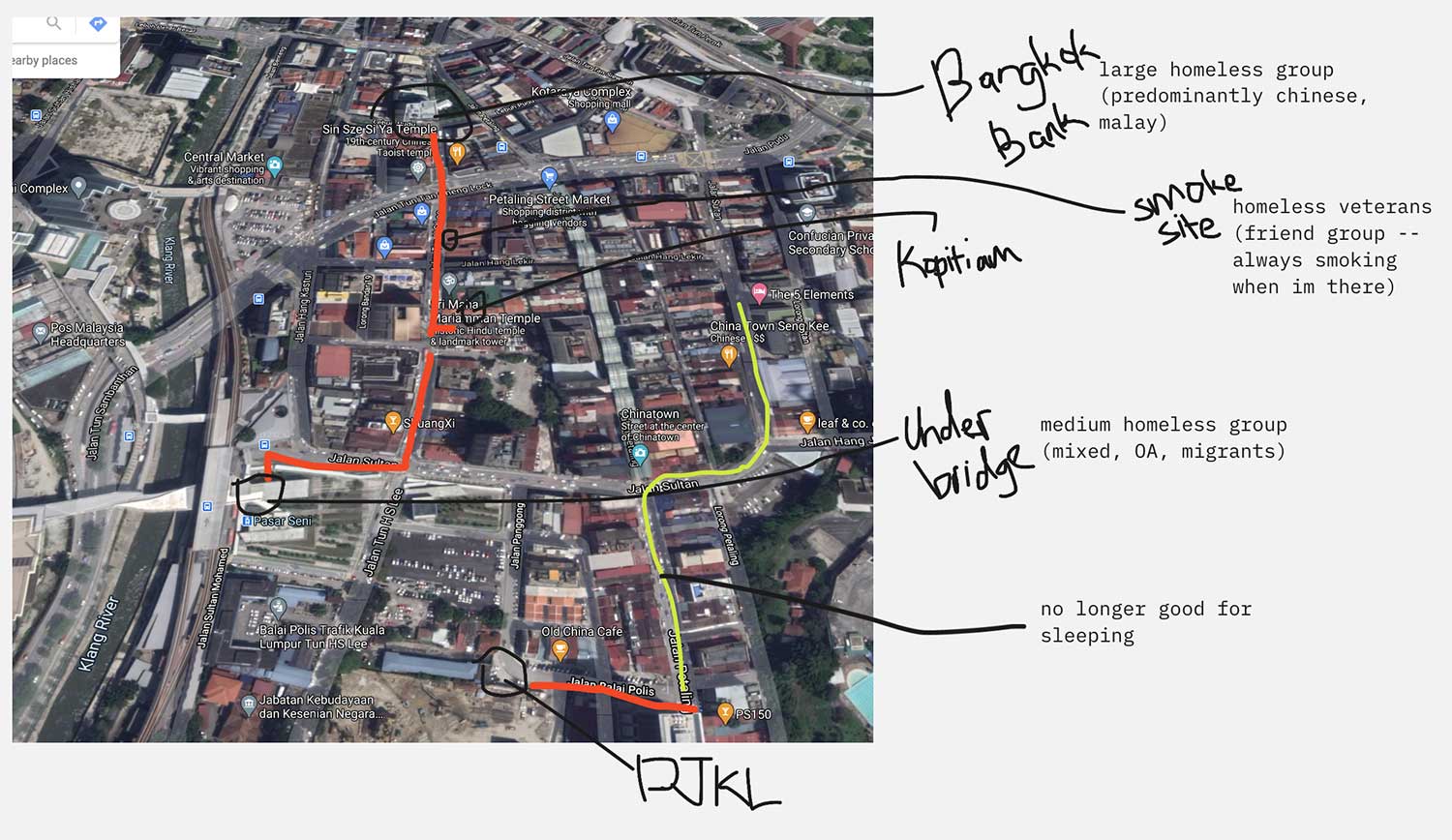

Peter and I would go on walks. Our job was to inform the networks of homeless people in the area about the Onn Loke shelter. Peter was a unique tour guide to Kuala Lumpur. On these walks, he offered a different interpretation of life in the city.

“以前那边还可以睡。现在他们做到美美,我也不敢去了。”

I used to be able to sleep over there too. Now they have made it so pretty, I no longer dare to go near.

Peter was referring to ThinkCity’s River of Life developments. A heritage project that aims to beautify, conserve, and rejuvenate social and economic activity in the city. The politics of heritage-making is complex, and questions of who’s history and who’s economic opportunity is being rejuvenated will arise. The material landscape of our ever-changing city is the site where these various individuals’ hopes, memories, and dreams are manifested, absorbed, flattened, diverted, and resisted.

For Peter, among his grandiose dreams of becoming a fisherman, getting a job at McDonalds, or just being able to go home, he also dreamt of housing by the River of Life.

“如果真的可以,我想跟妈咪Cindy组一个shoplot。楼下做一个免费restaurant — 你有多少你给多少。第二楼做一个cafe,给那些tourist啊,或者年轻人拍照;这里我们可以赚一点钱。第三楼我做个hostel可以给我的朋友们全部地方睡。”

“If it is really possible, I would like to rent a shoplot here with Mami Cindy. Downstairs, we would have a free restaurant — you pay as much as you want. 2nd floor, we will do a nice cafe for the tourists and young people taking photos. Here, we can make a little bit of money. On the 3rd floor, I will do a hostel so that I can let all my friends have a place to sleep.”

If Man during Modernism makes the world in our own images, then I can only lament that Peter was precisely the type of human whose images the world does not want to see. The many many dreams I heard on Petaling Street were always too (im)pure, too pagan, too ugly, too unproductive, and too dirty for the aesthesis of development¹¹.

¹⁰ Has anyone noticed that they renamed a section “Bulatan Merdeka”?

¹¹ If aesthetics refers to prescriptions of beauty, aestheses points towards your senses’ interaction with social and material space, and the gut understanding of what an environment ought to be.

Laman Tun Perak

¹² https://thinkcity.com.my/project/laman-tun-perak/

One of the contested ThinkCity green development projects that I learnt about was Laman Tun Perak. Located just north of Masjid Jamek, Laman Tun Perak sought to recreate a micro rainforest ecology, even including a motor powered stream. The stated vision that the “large variety of plant species… will hopefully attract more urban wildlife to counter-balance the bustling, often harsh, city environment¹².” I spoke to Danial [pseudonym] who worked at ThinkCity during the Laman Tun Perak initiative.

“Actually when we were planning it, we had to stand there and ask the public what they thought. One guy said, “who is going to stop here, it’s so hot.” Most people just considered it waste of money.

I think even ThinkCity doesn’t think it is worth the money. But let me explain: you don’t see as many physical projects in KL, because of lack of political willpower. So one of the easier ways is to… since they already have a type of relationship with DBKL, is to work on an easy proposal to work on. It’s tougher to work with individual shophouses. Working with authorities is easier to materialise and put together a portfolio.”

Danial recognises that these infrastructure projects are never quite straightforward. Manifestations of development are not only fuelled by top-down urban planning desires, but also the relational politics of working with the state actors, grant funders, residents and so on. No development is guided by a pure vision executed via centralised control.

The actual maintenance and use of the space too is subject to all kinds of uncontrollabilities. One of the unforeseen uses of a mini-rainforest in Chow Kit was when homeless people started showering there. Instead of wild birds, a different sort of “urban wildlife” came to seek refuge from the “harsh, city environment”.

“You know, Nam Heong chicken rice? Opposite there, there was actually public bath. But then, they closed it and now it is covered with zinc walls. Actually, even before [Laman Tun Perak] was refurbished, there was already homeless people showering there… but they got chased out. Now, it’s more of a passive space. Oh nice trees. Take a photo.”

Uncontrollability seeps from wild overgrown plants of Chow Kit’s “Angkor Wats” to wild overgrown humans who spill into spaces not built for them. What is the goal of attracting “urban wildlife”? We could deduce this by observing which specific natures and which specific humans are allowed to seek respite from the “harsh, city environment”. Perhaps we only welcome urban wildlife when it perches passive in a tree, providing a beautiful backdrop to fantasies of Pristine Nature.

And from here, when we think of the uncontrollability of the “wild”, we begin to understand that control is not “Human”; control is a specific human’s vision of orderly human-nature and human nature.

Conclusion

Chapter 1 argues that there is no pristine nature. Chapter 2 builds on this by exploring intended and unintended human relationships with nature, demonstrating the wider cast of actors it takes to co-operate. This chapter progresses the discussion by showing how working with a cast of actors will bring up the uncontrollable aspects execution, maintenance, and use of greenspace. Spaces take a on a life of their own, subject to the interpretations of all participants. It bears reminding the limits of the urban planner’s plans.

by Teoh Jia Chern