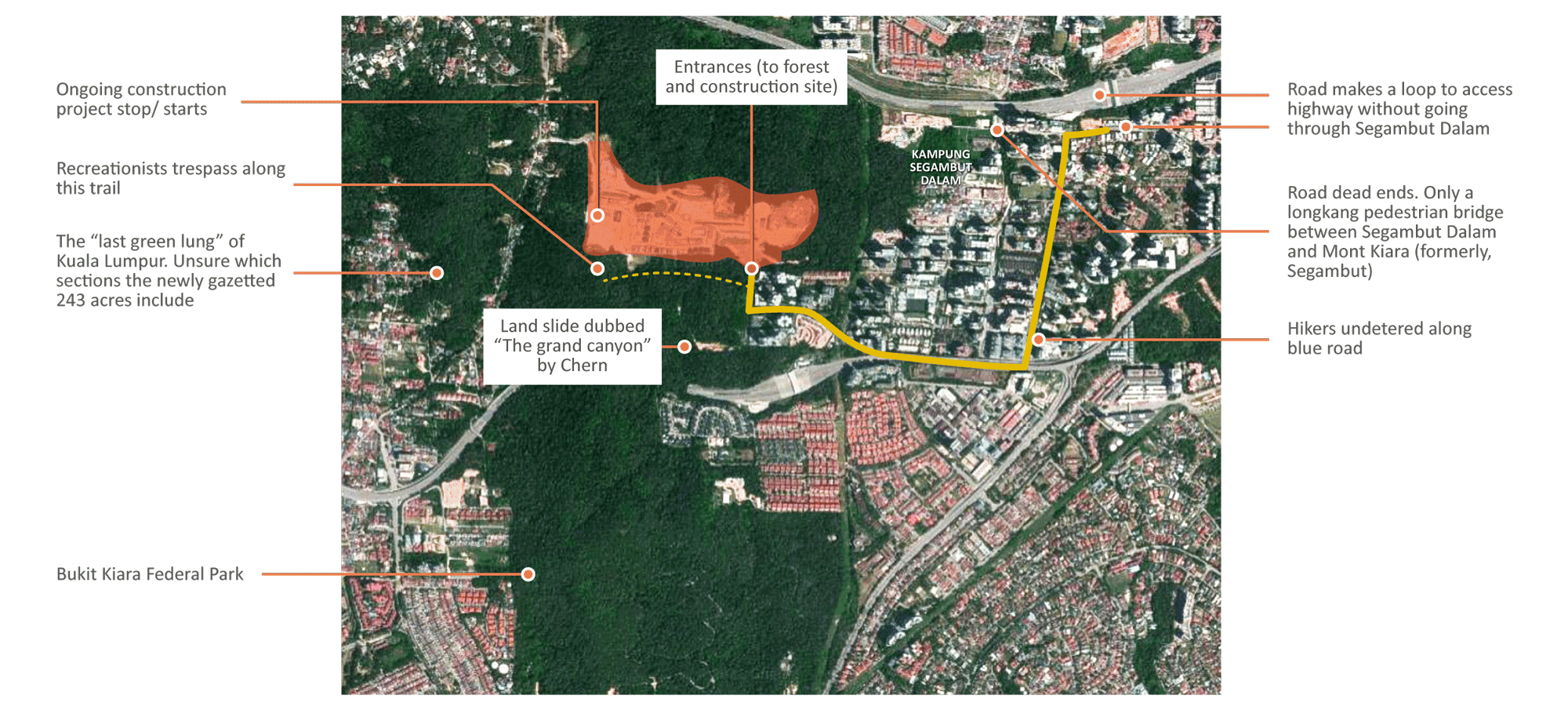

We begin at the development frontier of Mont Kiara and Segambut. I use the example of the “Last Green Lung” in Bukit Kiara to make the opening argument of this collection: there is no such thing as Pristine Nature in urban-biodiversity. The assumption of Pristine Nature narrows the possibilities of nature-based solutions in Kuala Lumpur, and can occasionally create unintended exclusionary effects on humans.

This chapter briefly outlines two transient populations in Mont Kiara/Segambut and Bukit Kiara. I introduce these two populations and their relationship with Bukit Kiara. I then provide a short history of (de)gazettement in Bukit Kiara. Finally, I close the chapter by discussing the tensions present in a traditional Conservationist approach.

Reflections

Gazettement assumes a Pristine Nature. Pristine Nature assumptions can occasionally lead to exclusionary “anti-human” conservation practices.

Sustainability is much more than about putting fences around Green things, it requires a supporting cast of human cultural and developmental ideologies around it.

There are many ways we use Greenspace. The value of a Greenspace extends far beyond the parcel of land it is on. There are plenty of cascading livelihood benefits, even in the city.

“By consistently presenting nature as an untouched wilderness, many nature documentaries mislead viewers into thinking that there are lots of untouched wildernesses left… This misapprehension then prompts people to build their environmental ideas around preserving untouched places and to embrace profoundly antihuman “solutions” to environmental problems, such as kicking indigenous people out of their homeland. In truth, wilderness doesn’t really exist.”

— Emma Marris, 12th April 2021,

“The Nature You See In Documentaries Is Beautiful And False”, The Atlantic

We begin at the development frontier of Mont Kiara and Segambut. I use the example of the “Last Green Lung”² in Bukit Kiara to make the opening argument of this collection: there is no such thing as Pristine Nature in urban-biodiversity. As Marris describes above, this assumption narrows the possibilities of nature-based solutions in Kuala Lumpur and can occasionally create unintended exclusionary effects on humans.

This chapter briefly outlines two transient populations in Mont Kiara/Segambut and Bukit Kiara. I introduce these two populations and their relationship with Bukit Kiara. I then provide a short history of (de)gazettement in Bukit Kiara. Finally, I close the chapter by discussing the tensions present in a traditional Conservationist approach

Ignoring (Good Advice)

It is 7am and there is a flurry of activity. The road up to Bukit Kiara is long and steep, but it does not deter hikers, runners, and cyclists. They pour out of their houses and apartments, past 163 retail park, past the Plaza Mont Kiara offices, past the Mak Cik warong’s opening day under the highway. The Recreationists march uphill with so much vigour, it is as if they are desperate to escape their enclosed offices and apartments (or maybe they have to return for an office Zoom call at 9am).

The entrance to the Kiara Hill trail is at end of the road on the hilltop. Some hikers choose to drive up to the park. In the same parking lot where hikers park cars, you may also notice construction workers readying for work and hopping on motorbikes.

But most people do not notice; they look at me quizzically when I ask,

“Have you err… seen those houses in the forest if you walk up that side trail?”

“Where got trail there, the trail is up this way la. Wah you wear slipper, sure or not?”

A quick search through online Kiara Hill groups using the terms “worker”; “foreign”; “squatter”; “construction” also revealed no results. Both online and offline, these populations do not seem to interact despite sharing an ecosystem. At 8am, as the Recreationists exit their cars and enter the forest for recreation, the Construction Workers hop on their motorcycles and enter the city for work. Some sort of temporal partitioning I guess.

Ignoring good advice, I follow the side trail up (in my slippers, of course). It is muddy and mosquitos frenzy. Motorcycle tracks have imprinted on the “hiking” trail. Monkeys hover above me, following in parallel along their treetop trail (okay, I should not have worn slippers).

² I can’t find who originally coined this term, but it has been used by Hannah Yeoh and in many media reports and conservation communications, such as: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ONDkIf1xIxo; http://www.themalaysianinsider.com/malaysia/article/bukit-kiara-last-green-lung-in-kl-under-threat#sthash.APuD8TrS.dpuf; https://www.thestar.com.my/metro/community/2016/02/06/bukit-kiara-to-be-gazetted-as-federal-park-next-year/; https://www.nst.com.my/property/2019/09/518946/maltons-scaled-down-project-start-next-year;

https://www.traks.org.my/post/82976902549/join-friends-of-bukit-kiara-inaugural-general

The Grand Canyon

After the developers came and cleared the trees from the hill, the rain came and cleared the hill from the land. Five years ago, the earth split into a deep canyon, and engulfed dreams of a luxury apartment. What is left behind?

If you wander far enough, and follow a strange uphill trail of soggy carpets flanked by rubbish and plastics, you might come across Arief (name changed) and his 4 year old toddler. Arief is an Indonesian construction worker who has lived in Kiara Hill since a failed development project left this gaping canyon.

“Apakah yang terjadi di sini?”

“Dulu sini juga ada pokok-pokok. Kita tumbang untuk membina sebuah jalan besar untuk lori keluar masuk. Tapi pada satu hari, hujan turun lebat dan tanah tiba-tiba runtuh.”

“Kau duduk sini ke?”

“Ya”

“Orang kat sini biasanya buat kerja apa?”

“Kerja kat Mont Kiara la. Ade yang berniaga, ada yang menjadi pembantu rumah, dan ada juga yang kerja kat projek pembinaan.”

I spend another 15 minutes with Arief as he explains to me which plants are edible and which are not. His son recreates in the background on this sun-baked hilltop. I wonder how fragile this earth is.

“Kalau nak keluar, ikutje jalan tepi sini sampai Kiaramas Danai.”

“Okay, terima kasih!”

“Hati-hati ya.”

Ignoring (Rain)

It is 5pm, and the hill is sparse. I watch a group of monkeys walk from apartments along electrical pole wires, and leap back into the thicket. They carry fruit home.

Rain dampens sounds as it dampens the ground. Soft pitter patter firmly but gently muffle highway engines. Even the birds quiet. What senses do we draw upon when we cannot listen? Despite a wave of rhetoric in International Development about participatory methods and community inputs, how do we understand those who refuse inclusion by us? Or perhaps, for the sake of their safety from the State, should not be included by us?

To sense why people hide from being heard, sometimes I turn to history³.

³ On a similar note: I would recommend Jame Scott’s “The Art of Not Being Governed” (2009) who challenges traditional History (typically centred around positivist narratives of Nation-State politics) by writing from the perspective of stateless peoples.

Decaying dreams of a construction project.

The Last Green Lung

How did we end up at the “Last Green Lung” of Kuala Lumpur? Last implies there were firsts, and seconds, and thirds. Let’s walk through a brief history of Segambut and Bukit Kiara. Of the initial 621 hectares acquired by the Federal Government in 1976, only 162 hectares of this Green Lung remains. And of this 162 hectares, only 111 was officially gazetted in late 2020. The initial 621 hectares was a compulsory acquisition from Ng Chin Siu & Sons Rubber Estate Ltd to be developed for public use.

If 621 hectares was the first Green Lung intended to be the “Hyde Park” of Kuala Lumpur, then the dreams for this Lung has slowly broken over the following decades. First into public projects: cemeteries, sewage plants, INTAN, the National Science Centre, and the Securities Commission. Then into private consumption: Sime Darby acquired land for its private KLGCC golf course and Berjaya developed the Bukit Kiara Equestrian and Country Resort, and a final section was developed into the Sungai Penchala Malay Reserve Land.

⁴ The old rubber estate extends down into today’s [Golf Course]

⁵ Taman Kiara Masterplan 1982, http://ofa.arkib.gov.my/ofa/collection/asset/1033646

⁶ Note: private residences can be developed for public good, but the properties developed on the Sungai Penchala Reserve are all multimillion ringgit Bungalows in prime location.

This is not the first time Bukit Kiara has been gazetted. A different section, Taman Lembah Kiara, was gazetted in 2004, but it was revoked in 2010. As of 2021, development squabbles over the previously gazetted Taman Lembah Kiara is still ongoing.

I spoke to Peter Leong, from Friends of Bukit Kiara, who has been involved in mapping the legality, geography, and history of area.

C: I’ve been wondering about the migrant settlements that you see in Bukit Kiara?

P: Oh yea yeah of course. There has been for a long time. There were other kinds of settlements there as well. In fact there still are.

Before the war, and maybe even after the war. It was actually owned by British capitalists. The Chinaman bought it over from the British. So the British actually turned it into a plantation at the turn of the century. So what happened was the British I think probably chased out the Malays from there.

For example, Kampung Sungai Penchala was originally in the Federal park, then they relocated the Malays into this Malay reserve. Which is actually in the valley of Sungai Kayu Ara. So there is this slightly puzzling situation, people wonder why Kampung Sungai Penchala not in the Sungai Penchala Valley. We reckon it was a resettlement.

Within the “Green Lung”, but outside of the federal park, many parcels in Bukit Kiara are actually the private property of various smallholders. But due to complex ownerships split among families, the lands have mostly been terbiar, and a sort of “customary right of way” has developed for people to walk through Bukit Kiara during the Recreationist Hiking Boom.

P: So nearer the village the land lot sizes tend to be smaller. Straight out the village, it is about 1 acre, then as you move further and further north, it increases to 2 acres, and then right at the so called “wild outskirts” side, it goes to 3 acres.

So generally in the types of development that you see, such as Serene Mont Kiara that cuts all the way from Ayuria to Penchala. That one came about via the acquisition by one man of 8 lots… So this guy who is Dato’ Seri Hishammuddin Hussein’s brother, acquired 8 of those lots, and then of course once the developer has created the critical mass by acquiring a number of adjoining lots, then they have the financial muscle to do all sorts of town planning submissions: to actually change the land use and then see to a level where it becomes profitable for him to develop. Whereas individual landowners of lets say 2 acres, you can’t do multi-story, because anything more than 2 stories cannot be built [on the agrarian titled land].

C: So as someone who has been involved in this space for many years, is it right for me to say that you are coming from an infrastructural/town planning perspective, rather than a pure conservationist outlook?

P: You see, ultimately, you cannot deny the rights of the title holders. They got the lands from the British as a resettlement program. The title broadly speaking allows 3 bungalows per acre or 12 people per acre. So if they were to actually build 3 family bungalows on their family land, then okay la…well and good, go ahead la. You are going to have all your dusun fruit trees around it. It will still be quite green. If everyone did that it’d be okay. The problem is that there are people like Datuk Harris Onn Hussein going around trying to buy over all the adjoining lots. And then once they develop critical mass, then they can propose increasing the land use density to DBKL.

Peter recognises the current conflicts over the Bukit, but does not constructs possible solutions through the binary framing of Conservation versus Development. Instead, he argues for the recognition of human presence, but asks for greater town planning in determining the appropriate human presences that should be on Bukit Kiara; what is at stake is the way that we use this land.

One of the ironies is that the Recreationists regularly “trespass” on these lands perhaps more so than workers like Arief. Arief lives by one of the large scale development that conservationists hope to stop. As an “ongoing” construction, it is the only way he is legally allowed to live in Bukit Kiara. Of course, legal life does not imply quality of life. Plastic wrappers and old gas cylinders breed an unusually dense amount of mosquitos. Arief shows me a well they dug to pipe water from. Electrical infrastructure is non-existent. Children cannot attend schools nearby, let alone have safe play spaces.

Discussion

- The first key theme is that we must recognise that Nature in the city has always had people and livelihoods attached to it. The Bukit Kiara “Green Lung” was not always a forest. It was a rubber plantation bought out by the federal government. A big question over current attempts to gazette will be: who are we gazetting out this time? A Pristine Nature framework denies pre-existing relationships between human and nature. In turn, it produces “anti-human” conservation solutions that will always put lives and livelihoods at jeopardy.

- Second, the lives and livelihoods put at jeopardy extend far beyond the populations that directly live on Bukit Kiara land. If we were to consider Bukit Kiara, Mont Kiara, and Segambut as an interconnected ecology, we would see two things:

- (1) the forestry of Bukit Kiara is integral to the mental wellbeing of Mont Kiara residents, making the “high value” economic activities (legal services, financial services, arts, fashion) of the area possible.

- (2) the forestry of Bukit Kiara is also integral as habitation for the workers in “low value” services (domestic workers, construction, delivery, cheap food for office workers) who maintain the domestic reproduction of households in Mont Kiara.

- Bukit Kiara serves the Recreationists and the Squatting Workers. It also facilitates the reproduction of each others lives even if both parties may not perceive it as so. Some sort of temporal partitioning I guess.

- Third, gazettement is unstable and always under threat. Rather than reading ongoing disputes over Bukit Kiara as as progress in gazettement, I interpret ongoing disputes through a history of degazettement. If the first key theme asks us to consider the populations who existed on a land before, here I suggest we also consider the future stewards of a forest. Fences and laws can protect a forest momentarily physically, but not culturally nor socially. A good green space also requires symbiotic humans and developmental ideologies surrounding it.

- Finally, a tangential but nevertheless key issue raised is: what might current approaches of Conservationists share with Developers? Ongoing disputes have been overwhelmingly binary; between “residents” and “developers”. However, there is a tertiary population not often accounted for. The squatter-residents of Bukit Kiara hide from Gazetteers and Developers, because their livelihood is tied to refuge in a disputed forest. The brief interlude on “Ignoring (rain)” opens up some questions about how our methods of inclusion may not be so inclusive at all. Framing the situation as Conservationists vs Developers excludes other people who use the forest.

⁷ During colonisation, the ideology of Conservation was used by the British to stop Malay smallholders from growing competing cash crops like rubber. Using the rhetoric of preserving Malay heritage, the British deemed rubber inauthentic to Malays, and thus illegal for them to grow. For longer historical context of how Conservation/Development was used to exclude in Malaysia , I would suggest Rudner’s “The State and Peasant Innovation in Rural Development” (1970)

Conclusion

When dreams are broken, they are left to decay as waste. Whether plastic bottles, construction workers, a golf course, or a Grand Canyon, these are the things that development/conservation dreams leave behind. Like composted soil, decay is necessary for constructing new relations and new desires.

The next chapter brings us to Bangsar, where we investigate decay through emptiness. Emptiness is the site where two unconventional greenspaces are developing via radically different forms and processes.

by Teoh Jia Chern