This chapter continues to follow these Transmission Towers south and westwards. It takes us along the edges of Bukit Gasing, past Tasik Taman Jaya, and across Sungai Penchala. Following these power lines inform us of the powers that de-line-ates the boundaries of space and the boundaries of category: hutan/taman, sungai/longkang

In this chapter, I want to help us draw attention to management of space. Hutan/Taman uses the layout of Bukit Gasing to tell us about the humans that manage it. It draws attention to political demarcations of the power to manage top-down. Sungai/Longkang reapplies this method, but follows how residents and a river transgress such attempts to manage their relationship. It adds nuance to this conversation about power to show how localised community cooperations still hold power to transform their surroundings, and produce unlikely sustainable ways forward.

Reflections

Material design of natural spaces reflect and reinforce specific types of relationships we have with Nature. It is worth considering whose cultural ideologies we are reinforcing.

But this power over space is not total. People will always defy design with their own interpretations and transformations of space. Instead of punishing transgression, a bottom up approach to working with nature requires us to work with humans. Interventions must all be grounded in the physical and social realities of a context.

Urban-Biodiversity is much more than about being “Green”; it is also about housing a multiplicity of human-natures and human natures.

Chapter 4 continues to follow these Transmission Towers south and westwards. It takes us along the edges of Bukit Gasing, past Tasik Taman Jaya, and across Sungai Penchala. Following these power lines inform us of the powers that de-line-ates the boundaries of space and the boundaries of category: hutan/taman, sungai/longkang.

Hutan / Taman

We think of maps as passive objects: they describe delineations of space. The WPKL/Selangor boundary of Bukit Gasing suggests otherwise. Here, we explore how political boundaries delineate humans and the ways we work with natures.

The WP/Selangor boundary line that slices Bukit Gasing into halves may seem arbitrary, but a quick look at altitude data suggests that the borders are informed by river basins. On the WP side, rainwater flows into Sungai Klang; on the Selangor side, rainwater flows into Sungai Penchala. Borders are informed by natural features, but these have also always been Human. Drainage basins mattered, because they reflect the agricultural and logistical resources offered by water. Human preoccupations are co-nstructed¹³ with natural features.

Walking across this boundary makes explicit the ways in which human constructs (of borders and categories) have an undeniable impact on material arrangements of human-nature. Of my three examples — (1) walking, (2) climbing, and (3) suspending — I will only go into depth on suspending to give you a quick sense of how these spaces differ.

¹³ On a similar note: I would recommend Jame Scott’s “The Art of Not Being Governed” (2009) who challenges traditional History (typically centred around positivist narratives of Nation-State politics) by writing from the perspective of stateless peoples.

Walking is messy with leaves, insects, and water on the ground.

Walking is smooth and elevated above ground.

Steps are built with trees fallen to clear the trail. It acts like a series of levees to prevent erosion of bare ground.

Bricks are brought in to lay steps. Each step is of uniform height.

Both sides of Bukit Gasing Trail feature suspension bridges. Both bridges are the key landmarks of their respective sites; they are the points where people crowd around in achievement. Suspension helps us manage uncertainty: uncertainty in terms of changing river flow, in terms of eroding river banks, and in terms of moving through a non-linear park space. Certainty is found in suspension above surrounding material space.

The Taman suspension is reinforced with concrete and steel: the path is solid and does not wobble. Multiple people can cross both ways at the same time. You are welcomed to linger over the river. Uniformity of passage is the platform for a variety of human expressions: on foot, on bicycle wheels or on wheelchairs. This uniformity is only made possible through establishing uniformity of surrounding space: foundations must be laid, riverbanks flattened and reinforced, and construction labourers must be scheduled along uniform understandings of time and salary.

The Hutan suspension is also a socio-material engineering feat of its own: ropes woven and reinforced by plastic sheaths. The path is flexible and it wobbles (this is perhaps the exciting feature for hikers). Only one person may cross at a time, and move in one direction. Human flexibility is integral to the functioning of a suspension bridge. Each foot placement must move in relation to the movements of mass (bridge, body, and prior action). A different sort of human expression is required to enable passage. Humans must become integrated into the system of the bridge in order to attain balance with our surroundings.

Now, the objective here is not to throw rocks at people and say: Hutan good, Taman bad. But to think about what these spaces may indicate about the goals of different populations and structures of management.

Although Hutan Pendidikan Gasing is under the purview of MBPJ in legal terms, MBPJ has largely played a supporting role to the real managers in practice: Friends of Bukit Gasing (FoBG). FoBG lay the trails, capture soil erosion, designate signpost sites, communicate with the public and so on.

FoBG management is explicit in its nature-oriented goals: “Its mission is to ensure the conservation of the Bukit Gasing forest and the surrounding areas¹⁴”. Although there is no mention of trail-maintenance or hiking benefits, it does not mean there is no function to Humans.

On the other hand, Taman Kerinchi falls strictly under DBKL management¹⁵. This was made formally recognised in 2012. DBKL note on their website:

“Rekabentuk pembangunan taman ini sangat mengambil kira keperluan pengguna dengan bercirikan konsep mesra pengguna, pembangunan mental dan fizikal dari sudut kesihatan diri”

The orientation¹⁶ is towards a biopolitical service of maintaining healthy humans. But although DBKL does not mention nature in any way, it does not mean there are no benefits to Nature.

Note that even these virtual spaces are arranged in a way that reflect both the material and the sociocultural arrangements of hutan pendidikan/taman rimba. Like the Taman suspension bridge, the DBKL website places human expressions within a modular website structure. Like the Hutan suspension bridge, FoBG operates on Facebook as a messy negotiation of commenters, public notices, spam, fun facts about trees, and decision making polls. It must be proactive to maintain balance and legitimacy.

Hutan/Taman contrasts two sides of this old rubber plantation. Although there are differences in Nature, I start with the premise that human political delineation is the dominant structuring factor of this material space.

As a public space, we can ask critical questions about the types of greenery we want in our city: whether hutan, taman, or anything between and beyond. What do these different material and virtual spaces mirror about our relationship with different managements? Do the desires of these people in managements reflect our own, or are they Humans we delineate from ourselves? The resonance we feel towards how a material space “should be” also reflects the sociocultural sensibilities we harbour in our respective communities — the diverse taken for granted understandings of human nature¹⁷. Just like we began to broached more deeply in Essay 3, we must ask: Who are these spaces built for and why?

FoBG Website

Taman Rimba Website

¹⁴ https://www.facebook.com/fobg.gasingkerinchi/

¹⁵ https://www.dbkl.gov.my/en/perkhidmatan/kemudahan-awam/taman-taman-awam/tmn_rimba_bukit_kerinchi/

¹⁶ Biopolitics is “to ensure, sustain, and multiply life, to put this life in order” (Foucault, Michel. 1976. “The history of sexuality: Volume 1, an introduction”. Translated from French by Robert Hurley. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 138.

¹⁷ We are taught that Culture is essentialised in colourful clothes and “traditional” rituals, but a deeper way to understand culture is: how we arrange and interpret material space, interactions, and social categories. In a political system based on representation, this makes all the difference in thinking about who represents us.

Sungai / Longkang

Nature changes and so do Humans. As such, our categories of Hutan/Taman and Sungai/Longkang are flexible to human understandings of nature. When our categories change, so does nature’s materiality.

During the establishment of Kuala Lumpur, Sungai Klang and Sungai Gombak was used for transportation. However, when the means of transportation was replaced by roads, rivers became “unproductive”. And as upstream logging disrupted the absorption qualities of the banks, river turned from “unproductive” into flood “threat”.

The river was demanded to quiet down and stay its course. “Stop meandering and do your job.” Concrete guards lined the river straight, and sure enough coerced the river to flow outputs of greater efficiency (measured in volume per second). Through the interventions of human activity, the river was bent into concrete straights, and became known as a Longkang: the river became singular in its function to prevent flooding by passing rain and waste water out of the city as quickly as possible.

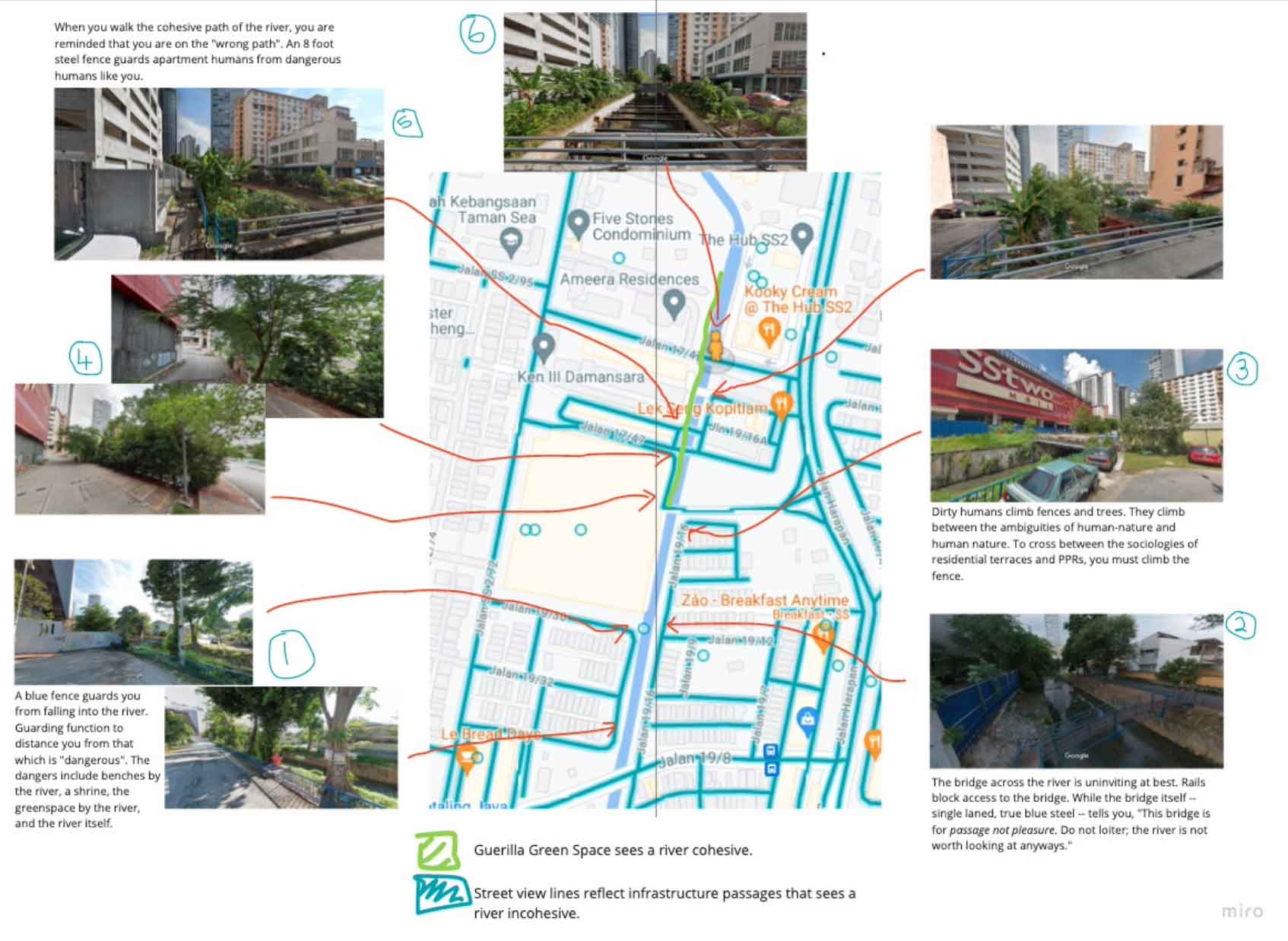

Sungai Penchala is not made to be in seen. Walking northwards along the river, the path is broken up and incohesive: you are guarded by a fence 3 meters from the river bank. Then, an abandoned shopping mall blocks the way, and you cross a small pedestrian bridge. The pedestrian bridge is a single lane metal bridge, you are not meant to loiter; the river is not worth seeing anyways.

For residents along Sungai Penchala, the river is not meant to be understood as a connection between upstream and downstream, but rather as delineation of space to be overcome. The built space around Sungai Penchala delineates cars from pedestrians and low income PPRs from middle income residential houses.

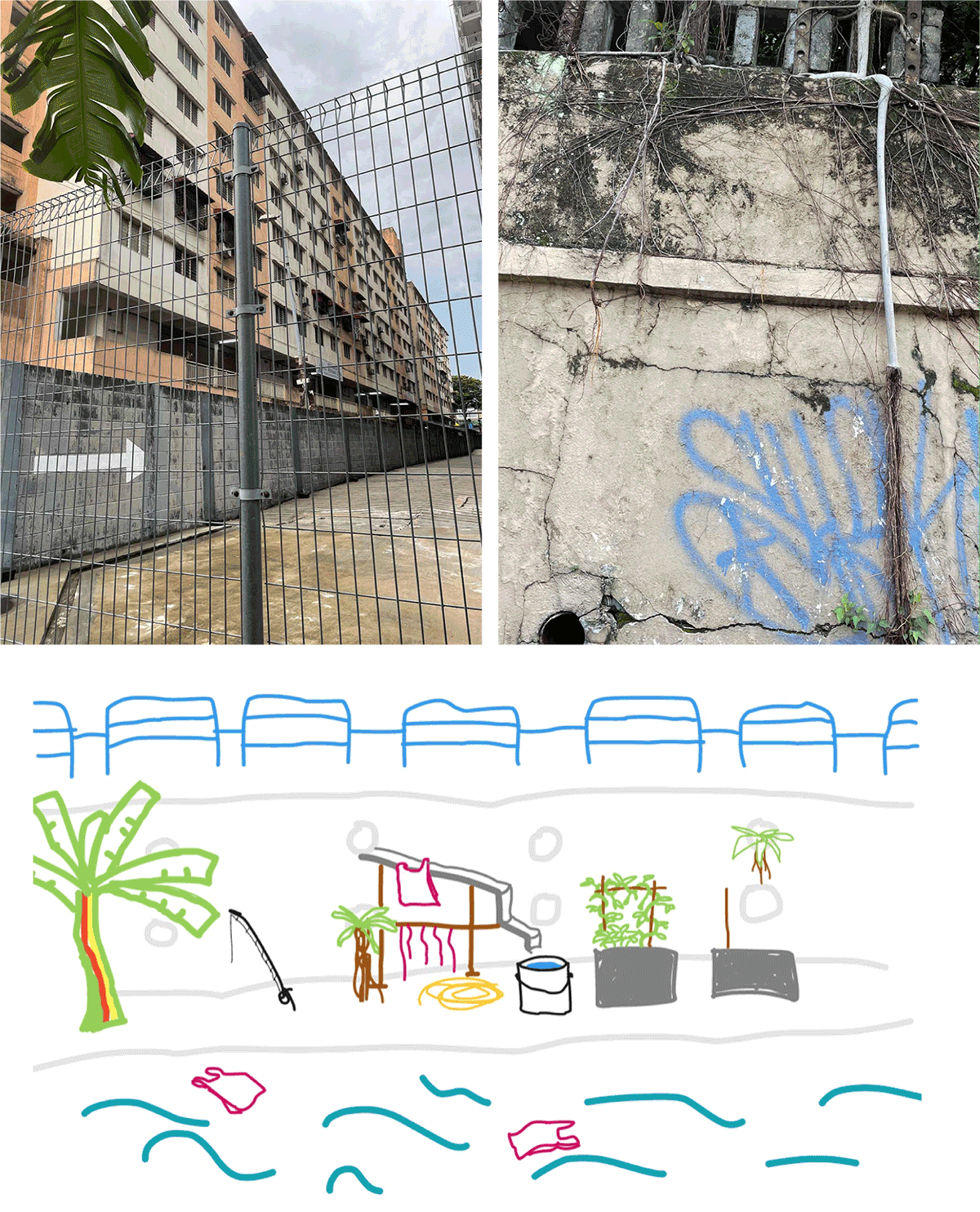

The road along the river pulls you westwards into the mall. To continue along the river, you are pushed onto the concrete river banks. But then suddenly, for a stretch of 1 kilometre, the river suddenly becomes cohesive. A small footpath takes you along the banks, past bayam in styrofoam boxes, under a little canopy, past banana trees, then under another highway where fishing rods that sit against the grand concrete pillars of the highway overhead.

Although the river becomes cohesive, you are reminded that you are not. Eight feet metal fences tower over to tell you that this is not “the path”. These fences guard humans in apartments from humans like you whose feet and fantasies tread off “the path”.

Across the river, a haphazard-looking concoction of pvc pipes and plastic bags are hung from the mouths of drain holes, coaxing the water into plastic buckets and bottles. The buckets and bottles feed the plants nurtured along this concrete river.

There is a certain irony to see plastic used to absorb and slow water as it flows down the drainage basin/system. Plant roots creep along and dig into the Longkang walls in eerie parallel to drain pipes. It’s almost as if roots, rivers, and drains were all designed to carry water.

And through a haphazard symbiosis of contextually-specific interventions by humans and nature, the Longkang slowly transforms from its singular function to move water as quickly as possible (measured in volume per second) into a river biodiverse in housing the various possible dreams of human and nature.

Discussion

- First, human delineations of power/authority shape the type of nature manifested. In turn, the perception of authorities — whether as Hutan or Taman — generates the nature constructed. One hill splits into two different types of urban nature that reflect two different human relationships with nature. I explore recurring patterns in material and virtual space¹⁸ to tell us about the human-natures who manage Hutan/Taman respectively.

- Second, the material space shapes our interaction with, and therefore relationship with nature. The brief analyses of suspension bridges exemplifies how physically crossing bridges reflect and reinforce specific relationships with Nature. I suggest the Hutan bridge demands integration with surroundings, whereas the Taman bridge enables detachment from surroundings. In Sungai/Longkang, the pathways and fences surrounding Sungai Penchala delineates and reinforces specific relationships with the sungai/longkang and between different residents.

- If Hutan/Taman teaches us to think about how delineations of power change material and social relationships between human-nature, then the third takeaway adds nuance to this conversation about power through Sungai/Longkang. (1) It points out the ways that “subaltern” humans and natures (those who are not “in power” or “in management”) still make their marks and occupy ownership over their surroundings. Fences and bridges enforce a certain relationship with rivers, but residents transgress these with their own interpretations of Sungai Penchala. I may not have experienced the cohesiveness of the river, had that path not been (illegally) built.

- (2) Recognising these types of ongoing bottom up efforts is essential to any urban planning. There are many parties who hope for the longkang to be transformed into an idealised river, but nostalgia for a river that is gone will only invite expensive and abrupt transformations of space. Perhaps if we begin from the bottom-up — acknowledging the current concrete realities of Longkangs and the social/ideological realities of those who live near it, we may find the unexpected possibilities that we need to truly move forwards. It may not look “pretty” or “green”, but plastic bags wrapped around storm drains offer a possibility for salvage, expression, and reconstruction.

- So the final and overarching theme to take out of this exploration of Hutan/Taman, Sungai/Longkang is that our cultural categories of Nature — whether we perceive it as Hutan/Taman or Sungai/Longkang — are flexible to change. They frame how we lay out space, just as the space frames how we utilise it. Power is contested both materially and socially.

- Tangential stylistic/methodological point: this chapter functions a little more like a practical exercise. I am attempting to advance the arguments of this collection by encouraging you to apply the themes brought up so far to your material surroundings. I want us to start moving outwards into our surroundings and think about our relationship with space. How much agency do we have over the spaces around us? What are the pathways to taking ownership over space?

¹⁸ ok, this is really because we ended up with MCO.

Conclusion

Chapters 1 has taken us past the point of developing fantasies of “pure” Green spaces. Chapter 2 explores some of the tensions of Humans working with Nature. Chapter 3 uses the human-organised nature to ask which humans are excluded from your vision of Nature. Furthermore, does Nature need saving at all?

This chapter moves forward with all these ideas, and more directly draws attention to which humans have a say about their surroundings. I add nuance to this conversation about power and management, through a short story about a river and resident who perhaps may guide us further along than any of these large scalable ambitions can.

Thinking about urban-biodiversity, what does it mean to work with a diverse system of humans-natures and human natures?

by Teoh Jia Chern